Disability History is a People's History of Collective Strength

People with disabilities and ideas related to disability are everywhere in American history.

The often arbitrary categories that identify people and the words that describe them have shifted across eras and locations. Disability activists have advocated, and continue to advocate, for changes to the built environment to increase accessibility, demonstrating resilience in a changing world.

Just as ethnicity and race are not Either/Or rigid classifications, neither is disability. A person is not always disabled or unable to do all things.

The often arbitrary categories that identify people and the words that describe them have shifted across eras and locations. For example, concepts of beauty and comeliness were different when physical injury, smallpox marks, and other scarring were more common.

Similarly, how or if a person uses words has not always been a universal measure of worth. People process information in many different ways. Likewise, a person might have left school to work in a mill before learning to read, used a language other than English, or had other differences that made their writing and reading atypical.

What constitutes “normal” changes from one era to the next. What constitutes a disability depends on who is judging and who is being judged. A lot depends on factors like where you are, what you are doing, and whether you feel safe or excluded.

For example, a beggar, a war veteran, a baby, and a musician may all have shared the experiences of being blind. Still, stigma, discrimination, and access to resources would differ for each.

Space is a critical factor in the history of disability. Artifacts capture both the dramatic and less apparent stories. Institutions, group homes, schools, nursing homes, camps, and independent living centers generated camaraderie, new ideas, rebellion, and change. People have been legally forced into and out of homes, hospitals, and institutions. Public health measures included quarantine for contagion.

The architecture and design of space shape social interactions and send messages about who is welcome. People who use a mobility device, such as a wheelchair, white cane, or crutch, have an intimacy with the textures of the road surface, the behaviors of other travelers, the location of light and signage, and similar landscape features. This awareness helps in navigation and safety. In the mid-20th century, institutions and local governments began adapting public spaces for accessibility. Activists lobbied for legislation and demanded the alteration of urban landscapes and buildings, often using concepts of Universal Design.

Activism takes many forms. It can be as complicated as a class-action lawsuit or as simple as wearing a T-shirt. Certain kinds of activism are unquestioned as part of social citizenship, such as voting, being informed, and attending school. People engage in other forms of activism, such as petitioning and protest, when rights are denied.

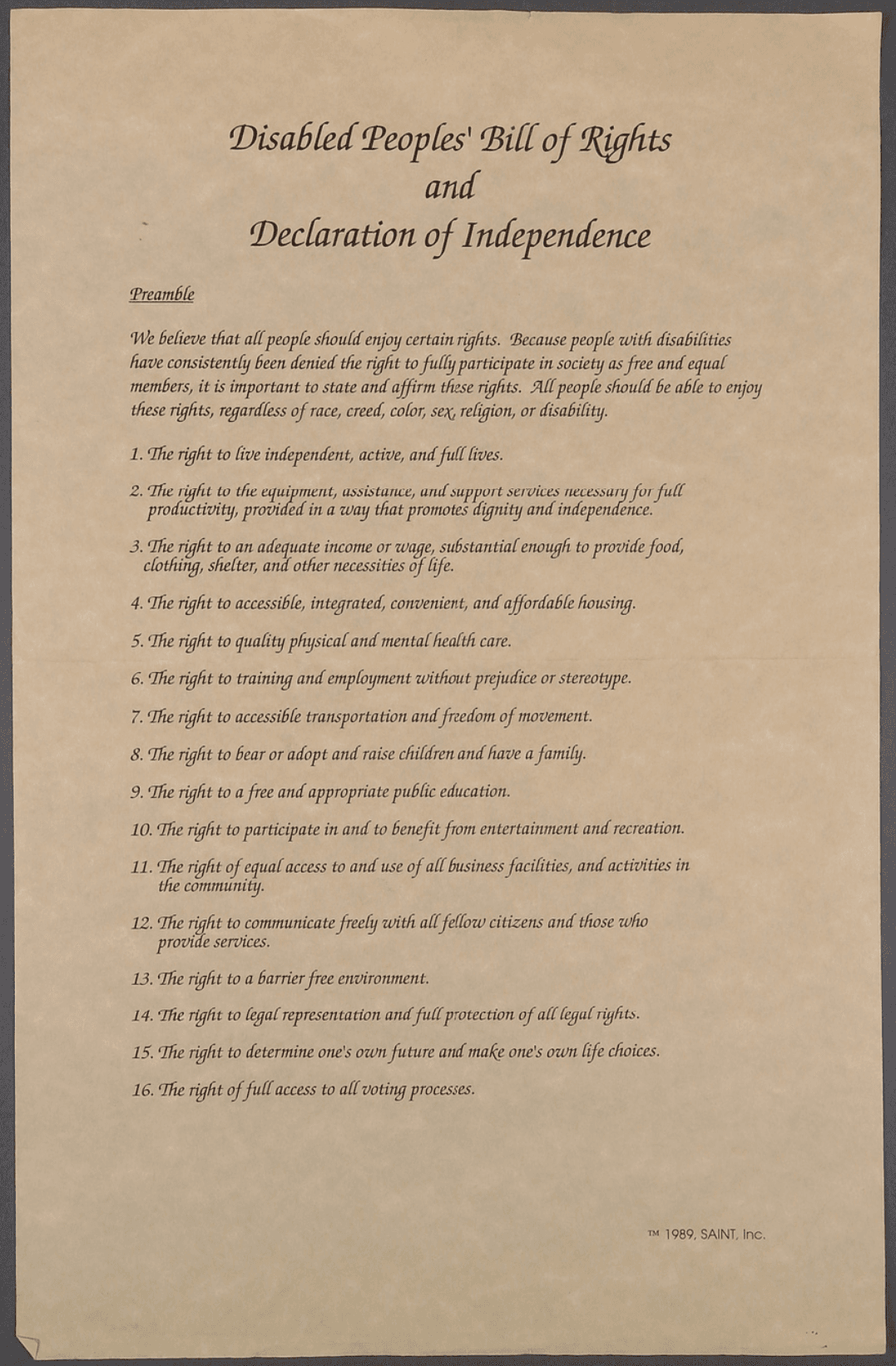

Disabled People's Bill of Rights and Declaration of Independence

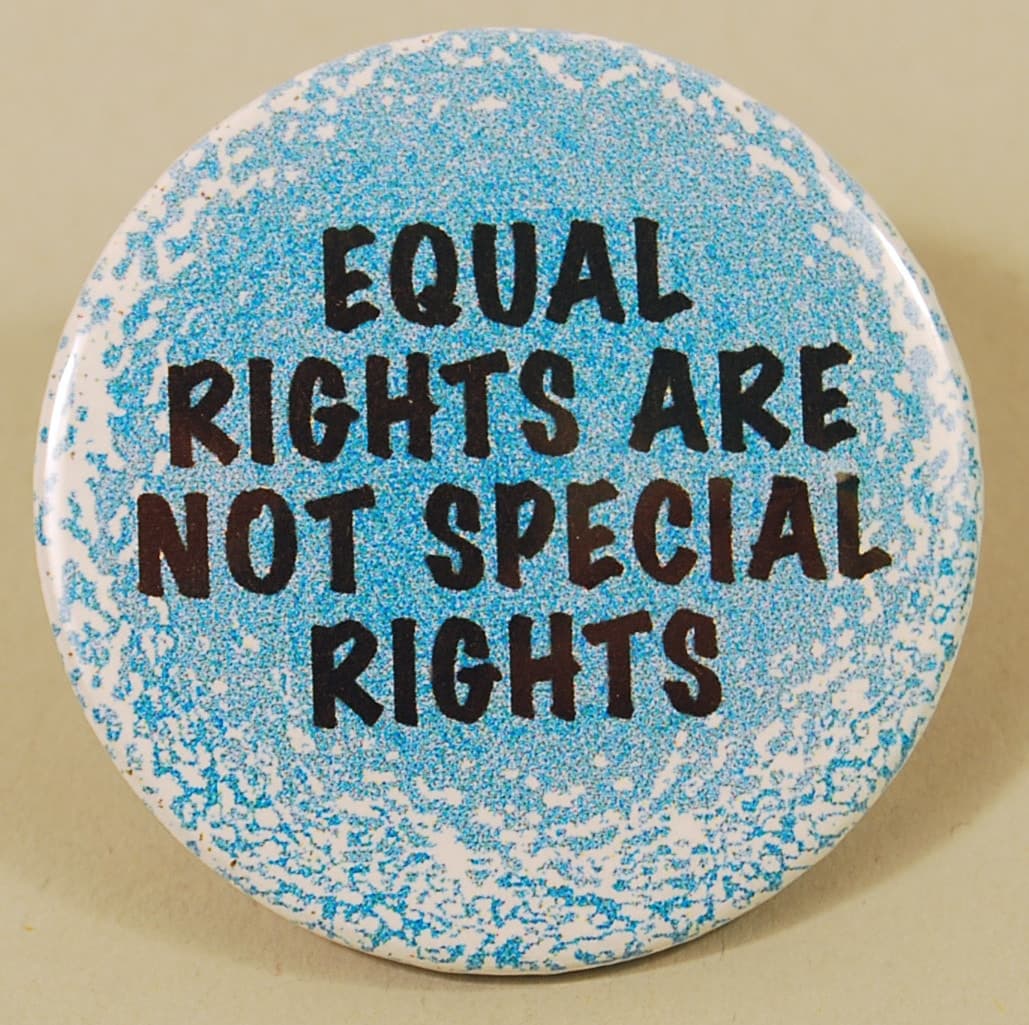

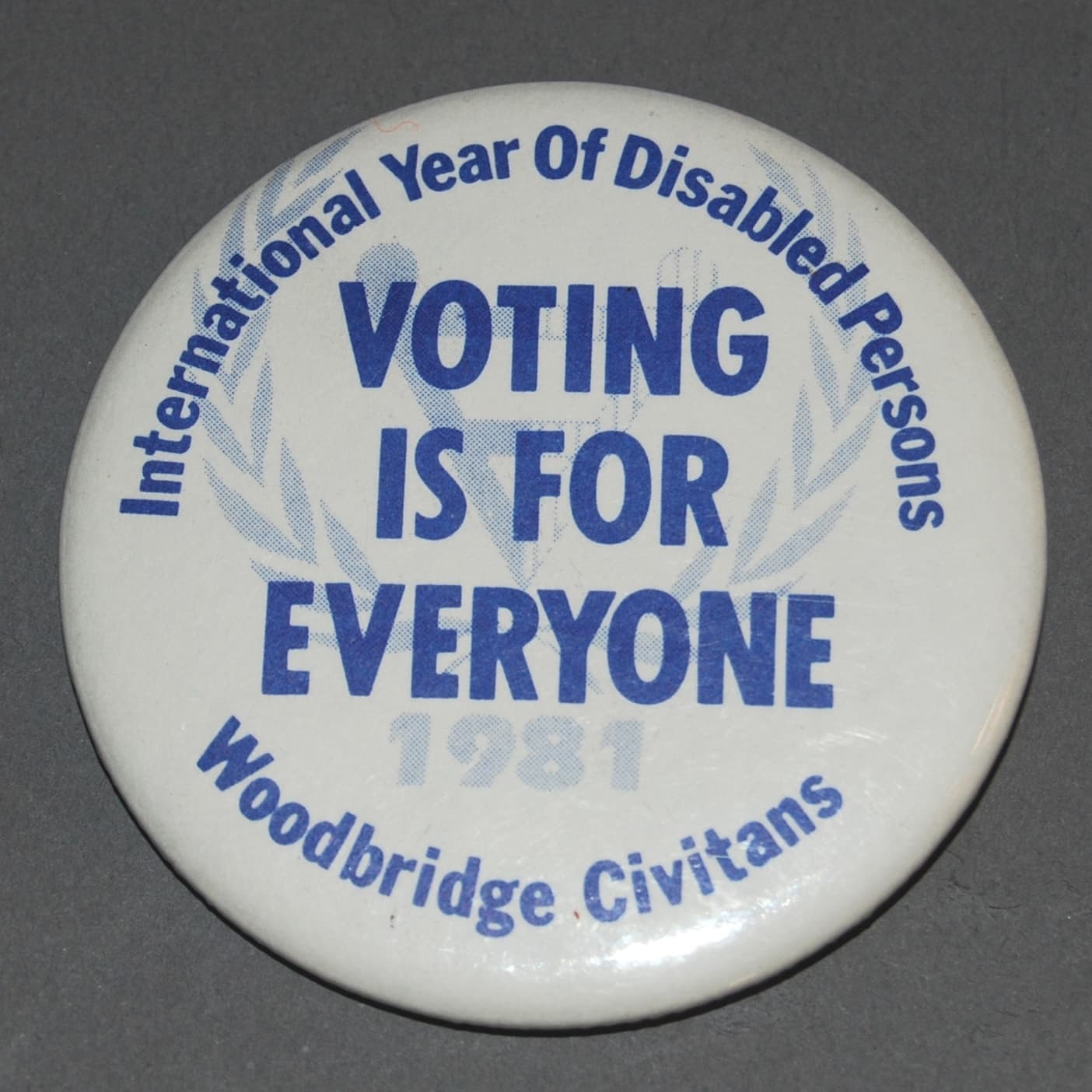

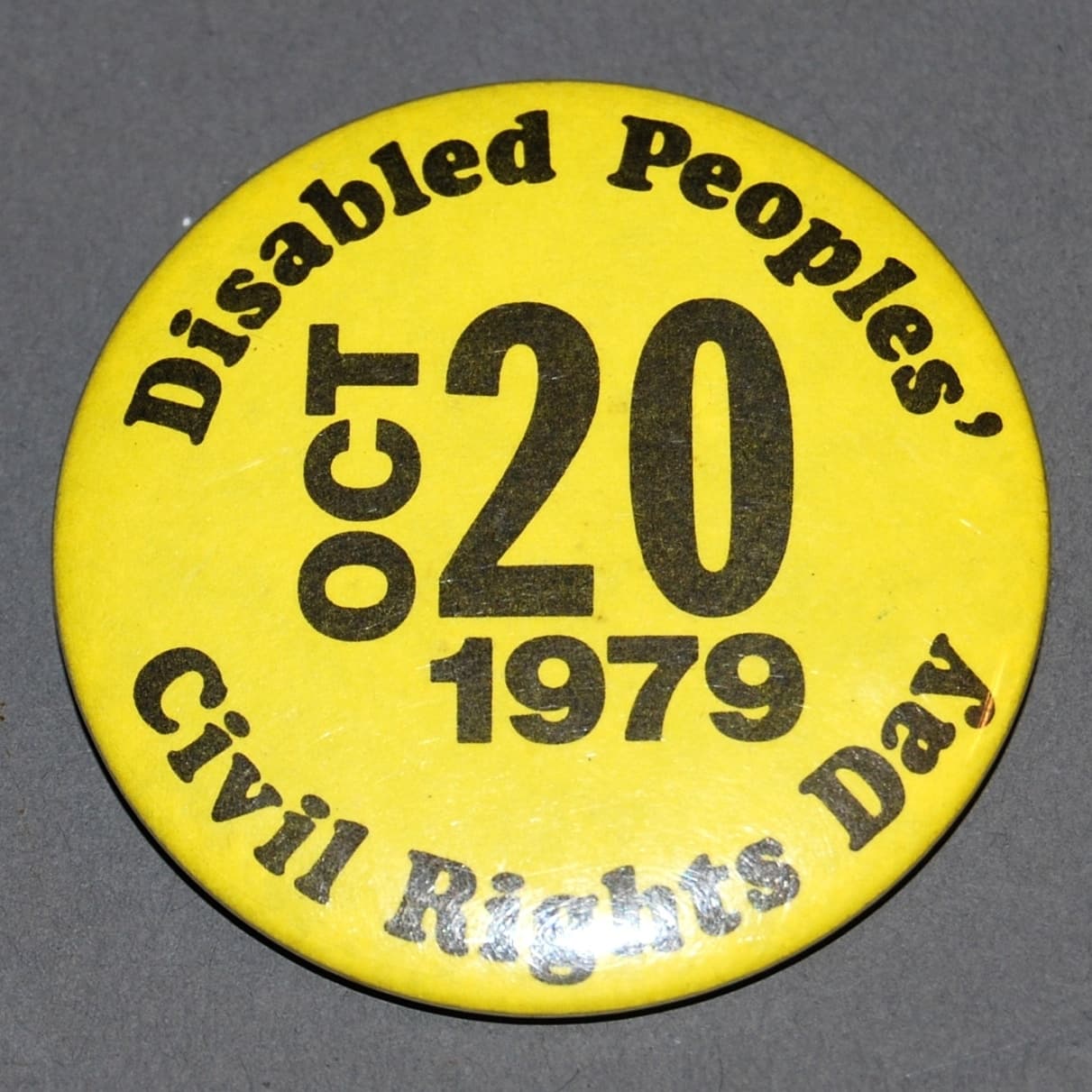

Source: National Museum of American HistoryPin-back buttons are powerful tools for activism, serving as effective advertising, fundraising aids for causes, expressions of personal beliefs, and methods for educational outreach. The Smithsonian houses numerous disability-related pin-back buttons, including the ones featured here.

button, Equal Rights Are Not Special Rights

Source: National Museum of American History (2010.0130.07)

button, Deaf Pride

Source: National Museum of American History (2010.0130.13)

button, Voting is for Everyone...

Source: National Museum of American History (2004.3055.01)

button, Disabled People's Civil Rights Day

Source: National Museum of American History (1999.0263.6)The notion that any one person is the single cause of any significant social change—that Abraham Lincoln alone freed the slaves—is a devastating stereotype which robs individuals of responsibility and credit, and actually inhibits social change... You can be a revolution of one. In your living room, in your family, in your community.